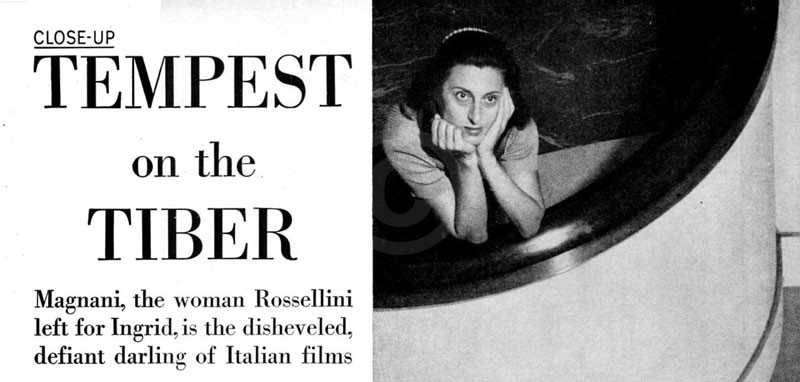

Magnani, the woman Rossellini left for Ingrid is the disheveled, defiant darling of Italian films

Every now and then along the Via Veneto – Rome’s Fifth Avenue – the cafe idlers are stirred out of their evening torpor by the rocketing passage of a green Fiat station wagon.

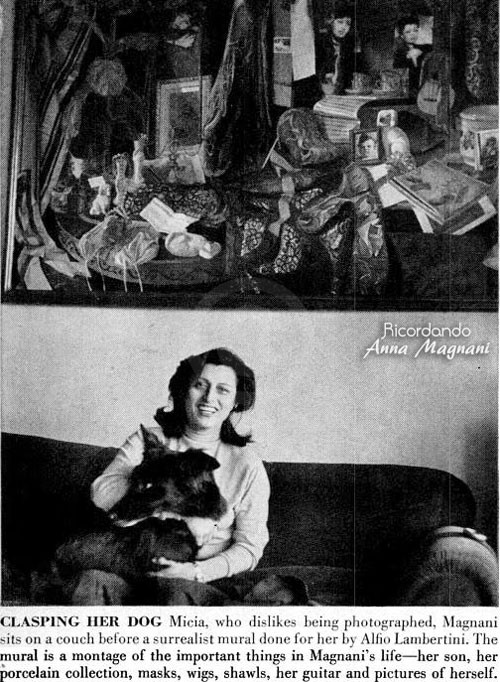

At the wheel is Anna Magnani, the greatest actress in Italy. With her is Micia, the most feared pet in Rome.

Micia is black as murder, with Baskervillian fangs and a fixed expression of savage mistrust. He snarls at anybody who ventures near his mistress. He has several times bitten Magnani fans clean through the hand.

But, even though Magnani has been sued countless times, she will neither muzzle the animal nor leave him at home.

In the way that people sometimes resemble their dogs, Anna Magnani, or “our Nannarella” as she is called throughout Italy, resembles Micia. And of this she is defiantly proud.

Her rank-growing hair, unconfined by hat or hairpin, is the same jolting shade of black.

She habitually dresses in black. Her big, strong teeth seem always about to bite. Emotionally she is never far from eruption. As she hurtles through traffic, she uproariously curses Micia, jaywalkers and the frustrations of life in general.

To Americans unfamiliar with Italian films, Anna Magnani may be known chiefly as the woman with whom Director Roberto Rossellini was in love before he discovered Ingrid Bergman.

But a poll along Via Veneto, which is frequented by film talent from every nation, would yield the consensus that Magnani is not only Italy’s but the world’s greatest film star.

This may be an overstatement of the case. However, in the four years since she emerged from comparative obscurity she has won the U.S. National Board of Review award for the best foreign actress (Open City, which Rossellini directed), the Venice Film Festival award for the best performance by an actress in any category (The Honorable Angelina) and the Silver Ribbon – the Italian Oscar – for the same two films plus an other Rossellini production, Love.

Anna Magnani has become one of the most impressive actresses since Garbo.

Magnani, whose sense of profit is also impressive, demands and gets the largest sums paid an actress in Europe. Since Italian personal-tax laws have many well-know loopholes, her net income cannot be matched even in Hollywood.

Magnani, whose sense of profit is also impressive, demands and gets the largest sums paid an actress in Europe. Since Italian personal-tax laws have many well-know loopholes, her net income cannot be matched even in Hollywood.

Magnani has attained fame and fortune – a long, tough haul from the rough-and-tumble neightborhood of her youth – with almost none of the equipment prized by more conventional stars.

Her formal education ended at the age of 14. The racy aromas of the Roman alleys still cling to her speech and manner. The only dramatic school training she ever got lasted less than two years.

In front of the camera she relies mostly on instinct. Although on the screen she can transmit by sheer dynamism the illusion of beauty and scorching sensualism, she lacks the sort of face and figure that ordinarily attracts men.

She is 41 years old. Both in the studio and away from it she disdains to interfere with nature.

She allows no hairdresser to tame her rowdy tresses, no beauty expert to tidy up her rampant curves. Finally, as the queen of the so-called neorealistic school of cinema (of which Rossellini is the king), she specializes in a class of role not generally considered to have wide audience appeal: she is the screen’s most convincing portrayer of the sad, seedy prostitute.

But the oddest aspect of Magnani’s pre-eminence is the inferiority of her vehicles.

Except for the three films that have won her prizes, she has appeared in few that measure up to Italian or even American standards of excellence.

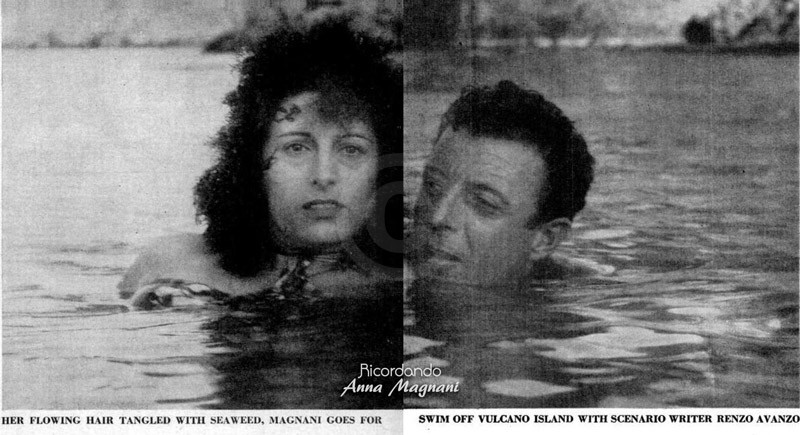

With Volcano, which was completed last August, coproducers Ferruccio Caramelli, who is sometimes described as a Roman Howard Hughes, and Panaria Films hope to have given her a really good film.

Dubbed in both languages, Volcano is the first film made by Italians primarily for the American market. The cost topped $750,000, a whopping figure for an Italian production.

Williams Dieterle was imported from Hollywood to direct it, as well as Starlet Geraldine Brooks to play the ingénue lead, and Erskine Caldwell to write the English dialogue.

It had its Italian premiere last week, will have its New York premiere early this spring.

Whatever the over-all merits of Volcano, Magnani’s appearance will very likely pack the house.

The essence of this transcendent allure has probably been defined best by Dieterle.

“Magnani”, he said, “is the last of the great shameless emotionalists. You have to go back to the silent movies for that kind of acting. Most of the modern stars try to cultivate understatement and subtlety, but Magnani pulls out all the stops. The style is so old it looks new”.

A startling example and one which would probably run afoul of censorship if it were shown in this country is the movie Love.

It consists of two unrelated studies of feminine passion.

In the first part, an adaptation of Jean Cocteau‘s one-act, one-character tear-jerker, The Human Voice, a jilted woman spends 20 minutes on the telephone pleanding with her faithless lover. It has usually been performed in a low, sophisticated key. Magnani sheds Niagaras of tears, howls like Medea and rolls on the floor in her anguish.

The second part, entitled The Miracle, pictures in unsparing detail the story of a peasant girl with religious dementia who takes a passing stranger for Saint Joseph. Playing her with wine, he seduces her. During her ensuing pregnancy she believes she is bearing the Christ Child and, as her time approaches, she crawls up a mountainside to an abandoned nunnery where she gives birth, moaning, “Bambino, bambino…“

In the seduction scene Magnani conveys the combination of religious ecstasy, intoxication and physical transport by uprooting grass and chewing it furiously.

Off the screen Magnani often flaunts her emotion with equal fury and abandon.

At the 1948 Venice Film Festival, for example, when Love failed to win her an award (it went instead to Jean Simmons for her performance as Ophelia in the Olivier Hamlet), Magnani tore through the Hotel Excelsior like a typhoon, screaming, “Goddam them, they didn’t give me the prize!”

She has a proprietary attitude toward the men in her life which excludes even their male associates. When one of them drove off after a lover’s quarrel she chased him in her own car up and down the Via Veneto until she could lay her wheels on his rear fenders and nudge him to the curb.

To the bemusement of onlookers she thereupon demonstrated again her mastery of eloquent, fluent profanity.

But her hair-trigger emotions can also produce spectacular gestures of generosity. Moved to tears by the plight of some convicts in a Sicilian jail, she sent them 40,000 lire.

When an electrician on her set contracted ulcers, she footed all his hospital bills. (Let the same electrician flub a light cue while she is performing and her fury is likely to cost him his job).

But she is, in other respects, almost a penny pincher, visiting the smart shops and restaurants infrequently and entertaining cautiously.

But she is, in other respects, almost a penny pincher, visiting the smart shops and restaurants infrequently and entertaining cautiously.

Magnani is a profoundly, incurably melancholy woman. Yet, with the peculiar split personality of the born actress, she is able to detach herself from sorrow, in a sense enjoy it and explore its histrionic content.

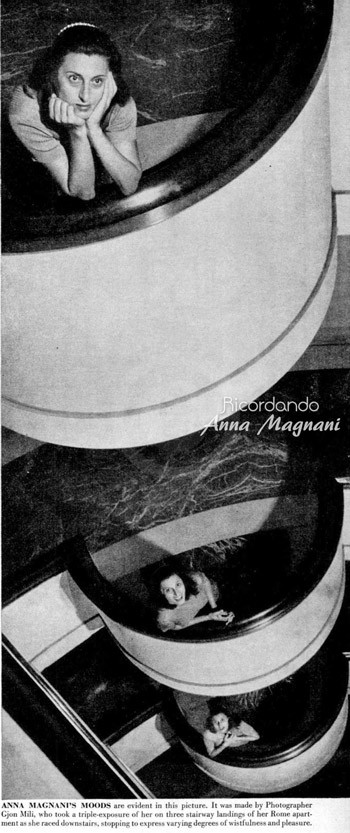

When Rossellini transferred his affections to Ingrid Bergman, Magnani’s grief was Sophoclean.

She harrowed her sympathizers with all-night analyses of ther suffering and threatened suicide. She begged newspaper reporters, “Please, please, leave me alone with my tragedy.”

She also promised, “I will break every plate of spaghetti in Rome over his head.”

Many observers feared for Bergman’s physical safety should the two women ever meet. They never did, and presently Magnani’s mood lapsed into one of morose resignation.

When Bergman finaly flew to Rome, Magnani enacted, quite spontaneously, her own version of The Human Voice. Telephoning an intimate member of Rossellini’s circle at 2 o’clock in the morning from London, where she had gone to attend the opening of one of her films, she asked, “Has she arrived?” “Yes”, said the friend. The dialogue continued as follows:

MAGNANI “Mannaggia! (freely translated, ‘Goddam’) Is she pretty?”

FRIEND “Yes”.

MAGNANI Mannaggia! Was he waiting for her at the airport?

FRIEND “Yes”.

MAGNANI “Mannaggia! (a pause) Did they kiss?

FRIEND “Yes”.

MAGNANI “Mannaggia! (a long pause) Did he drive her to her hotel?

FRIEND “Yes”.

MAGNANI “Mannaggia! (a pause of a minute) Did they go by the old Appian Way, in the moonlight?

FRIEND “Yes”.

MAGNANI “Mannaggia! (she hung up)

During a game of Truth and Consequences staged for laughs by the Volcano company, Magnani replied in answer to a pointed question about Rossellini, “I have never been happy in my life”. “Come now, Anna”, Dieterle chided her, “you were happy as a lark the other day”. She exploded: “How dare you tell me I was happy! Never, never in my life!”

FATHERLESS, MOTHERLESS

Without doubt, many of the simplest requirements for happiness have eluded Magnani. She was born out of wedlock to a girl of the working class, Marina Casadei. Before she was a month old her father, Francesco Magnani, disappeared. People close to the actress feel that this rejection by her father explains her ambivalence toward men, whom she cannot live happily with or without.

In her third year her mother too went away to make a fresh start in Egypt, and Anna did not see her for 12 years. She rarely refers to her mother today and when she does it is with an undertone of resentment.

“I am really grateful to Marina”, se once said. “Had she been the usual sort of mother, I would probably never have become an actress. But she was violent, willful and romantic – I take after her. Egypt was her escape. Acting is mine.”

Anna was entrusted to the care of grandparents, to whom her mother sent money from Egypt for her support. The Casadeis were a big, brawling, joyous but poor tribe who lived precariously on the wrong side of the Tiber in a district as colorful as a Persian bazaar.

Although Magnani has long since moved to more elegant quarters, she is irresistibly drawn back to the scenes of her girlhood. She likes to dine there of an evening in one of the local restaurants, raucously swapping ribaldries with old friends who thee-and-thou her as one of them. When “our Nannarella” departs, the police have to clear a path through the crowd.

Anna was a plain, frail child with a forlornness of spirit that touched her grandparents. They pampered her, often depriving themselves to provide her with good clothes and food. She fared so much better than the other children of the neighborhood that they would tear her dresses in envy and taunt her with epithets such as “Dung Princess”.

But then as now she felt more at ease among earthy companions than refined ones and unfailingly cosied up to the toughtest kid on the block. “I am antibourgeois,” she proclaims defensively. “I hate respectability. Give me the life of the streets, of common people.”

This antipathy toward polite society occasions many a display of brusque incivilty. An elderly lady, having met Magnani at a theatrical function and learned that she had a son, observed kindly, “I never think of you somehow as a mother.” Magnani replied, “I never think of you somehow as a lady.”

One day a mongrel dog bit Anna severely on the cheek, sending her to the hospital. Far from fearing dogs thereafter, she still be friends them with frenzied enthusiasm, professing to value them above humans.

One day a mongrel dog bit Anna severely on the cheek, sending her to the hospital. Far from fearing dogs thereafter, she still be friends them with frenzied enthusiasm, professing to value them above humans.

She is continually rescuing stray curs in the street, picking the fleas out of their hair and creaselessly seeking homes for them. She has not spoken for months to friends who declined to adopt one of these foundlings.

When Dieterle ordered a barking dog banished from Volcano, Magnani sulked until it was brought back and fed. The only known exception occurred recently when a barking watchdog in a monastery below her apartment kept her awake all night.

She threatened the monks that if they did not keep the dog quiet she would parade stark naked on her balcony.

So the monks kept the dog awake all day, the dog slept all night and Magnani kept her clothes on. Her present menage includes, besides unhousebroken, shares her bed; Musina, a Persian cat; four kittens and a nameless turtle.

When she was 7 Anna attended a French convent school in Rome where she learned to speak the language well. She also studied the piano, which she still plays expertly. But her most expressive musical instrument is her own resonant, somber, contralto voice.

At parties or alone she likes to sing bittersweet songs in romanesco (Roman version of Brooklynese), accompanying herself on the guitar. Those who have heard her treasure the experience more than any film she ever made.

At the convent, too, she acquired her passion for acting when the nuns staged a Christmas play. The remittances from her mother were just enough to cover tuition in a dramatic school, and at 17 she entered the Eleonora Duse dramatic school. (A critic later alluded to Magnani as “the peasant Duse”)

Midway through the course she was interviewed b the actor-manager of a touring repertory company who needed extras. She jumped at the chance, although the pay was only 25 lire (88¢) a day. She never again accepted help from her mother.

There are few apprenticeships seamier than that offered by the Italian theater. Magnani was sparel none of it.

For the next few years she shifted from one tattered troupe to another, seldom earning a living wage but gradually getting better parts.

The ordeal instilled in her an appreciation of money which has since caused many a producer to toss in his sleep.

At the outset of her film career she would report to work with hand outstretched and keep it so until she held her day’s pay – in cash, no checks.

She can now bring herself to wait until the end of the week, but her first move upon undertaking a new film is to find the man in charge of incidental expenses, turn her purse inside out to show that it is empty and warn him, “It’s up to you.”

The wardrobe bill she submitted for Volcano, in which she wore mostly peasant garb, ran to two milion lire ($3,200).

In 1933 Magnani was doing experimental plays in Rome with an earnest little art group when Goffredo Alessandrini, a movie director of the jodhpur-wearing, megaphone-wielding tradition, saw her act. Excited by her fieriness, he hurried backstage.

He was of a prominent, wealthy family and as gallant as a guardsman.

Two years later they were married. Magnani immediately retired to devote herself exclusively to her husband. “I suffered horribly away from the theater”, she says, “bub I could bear to be away from Goffredo even less”.

The idyll was short-lived. Alessandrini’s attentions soon strayed to other woman. “You know how it is”, says Magnani with a forbearance she did not feel at the time, “a man gets tired of the same woman”.

Her interests at home disappearing, she went beck into the theater to portray a gallery of delinquent heroines – Carmen, Maya, Anna Christie. She was not a sensation, but few actresses ever are in Italy, where the people take their drama haphazardly.

Rome supports barely nine theaters, and three weeks is an average run for any play.

Where Magnani finally achived a smashing success on the stage was in the sceneryless reviews organized by the city’s leading actors during the American occupation when shortages made legitimate plays difficult to stage. Singing, dancing and reciting racy monologues, she captivated GIs who understood not a word of romanesco dialect.

Magnani had profited b her retirement to study both stage and screen acting from the front of the house. What she saw strengthened her leaning toward neorealism.

“The classic poses, the cultured accents – tripe!” she jeers. “For me, acting should be as natural as life”.

Before her marriage had cooled entirely, she had told Alessandrini, “I want to act in movies. I know I’m ugly, but must movies show only beautifiul, well-dressed women? Why not ordinary, down-to-earth women for a change, women of the people – like me?”

“Dismiss it from your mind, my dear”, Alessandrini advised her loftily. “The cinema can never be for you”.

She promptly landed a role in a very down-to-earth film indeed, entitled A lamp in the window. She has since appeared in 19 others, the majority of them equally down-to-earth.

Today from hapless women the country over she receives begging letters which frequently begin, “You who understand us…”

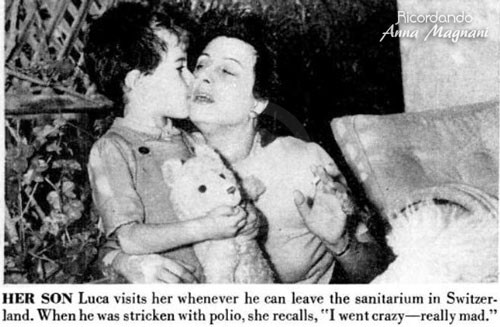

In October 1942, after she and Alessandrini had finally separeted, Anna bore a son. She named him Luca and gave him all the maternal devotion that she had missed in her own childhood.

HER SON IS CRIPPLED

The next tragedy to befall Magnani filled her bitter cup to the brim. In 1944 there were 48 cases of polio in Rome. Luca, then 18 months old, caught the disease.

Today, at 7, he has not regained the use of his legs and he now has to spend most of his time in a sanitarium for treatment. He is otherwise a handsome, sturdy youngster, with his mother’s dark, wild hair and luminous eyes.

The thumping salary demands for which his mother’s dark, wild hair and luminous eyes.

The thumping salary demands for which Magnani is notorius are dictated by Luca’s needs rather than by personal extravagance.

In the early stages of his illness she spent most of her earnings for specialists and hospitals. When it was determined that he could not walk again, she resolved to accumulate a fortune that would shield him forever from want.

Not long ago she stood watching a legless veteran drag himself along the sidewalk. She said afterward, “I realize now that it’s worse when they grow up”.

Then came Roberto Rossellini. “I thought at last I had found the ideal man”, she says. “He had lost a son of his own and I felt we understood each other. Above all, we had the same artistic conceptions”.

But Rossellini proved to be as violent, volatile and possessive as Magnani, and far less ingenuous. They wrangled constantly, partly over feverish dreams of bold film venturese, partly in jealousy.

In fits of rage they threw crockery at each other. Following one of these battles, they happened to turn up at the same party. At sight of him Magnani roared, “On your knees, miserable one, and beg forgiveness”! To his knees he sank and she was momentarily appeased.

On the professional level, however, no two artists ever complemented each other more sensitively. Magnani would project his ideas intuitively, almost before they were expressed, while from scene to scene Rossellini would modify his characters and story line as he sensed her perception of them.

Most gratifying to Magnani, he indulged her swift, unpredictable humors which impelled her now and again to stalk off the set in the middle of a take or not show up for work at all. “To act, I must feel the mood”, she insists. “It cannot be forced. Roberto always understood that”.

On Rossellini’s assurance that he was preparing the crowning vehicle of her career, Magnani turned down offers from other directors for a year, some of them guaranteeing her as much as 30 million lire. But Rossellini prepared another movie and presented it to Ingrid Bergman.

Since the breakup Magnani has lived in a seven-room terraced flat in Rome, where she wanders about in lonely restlessness. She is, says a friend, “like an animal in a trap, gnawing on its own leg”.

She does not encourage easy friendships. When miffed, she sometimes walks away from a dinner party, smashing plates on her way out. “Sometimes”, she says wistfully, “I think I frighten people”.

SUPERSTITIONS, FEVERS AND ACHES

She is as superstitious as a gypsy. She consults astrologers (she is a Pisces subject), goes in for numerology (her birthday is March 7, and she attaches mystical importance to the number 7) and claims to be clairvoyant herself (“I foresaw the Bergman affair before Roberto even knew her”).

She cannot retire at night unless her shoes are aligned under the bed. She believes that a dog dying indoors bodes ill to some human relationship in the house. “With Goffredo and Roberto it was the same”, se said. “Just before the final parting a dog died”.

And always she is prey to mysterious fevers and aches which she will discuss exhaustively. As she arrived on the Volcano set one day, Dieterle called out the casual salutation, “How are you, Anna?”, she announced solemnly, “Ninety-eight point nine”. Never eating or drinking much, she often subsists for long stretches on black coffee and cigarets. The resultant stimulation, she believes, is good for her acting. She sleeps poorly, reliving the day’s calamities.

“My nights are appalling”, she says. “I wake up in a state of nerves and it take me hours to get back in touch with reality”.

Magnani’s apartment reflects her flight from orthodoxy. There are a dozen porcelain poodles, a 50 pounds armored puppet astride an empty saddle, tinted glass balls heaped under a Bechstein piano, the red velvet bed Rossellini gave her, bisque figurines illustrating the Nativity and an immense surrealist painting of Magnaniana which includes a telegram from Bernard Shaw granting her permission to attempt Pygmalion in romanesco.

To Magnani the success or failure of Volcano means more than professional prestige. Her woman’s pride is at stake. For Volcano was produced in circumstances deliberately calculated to invite comparison with the Rossellini-Bergman film, Stromboli, a strategy originally inspired by a befuddled chambermaid in the New York hotel where Producer Caramelli was stopping last winter.

“Shame on Ingrid Bergman”, he heard her mutter over a gossip column, “stealing that poor Mrs. Magnani’s husband!”. Taking her sentiments to be those of the American masses, and shrewdly appraising the publicity assets of a glamorous international triangle, Caramelli launched what amounted to a counterproduction.

The two films are similar in locale. The harsh, sparsely populated Aeolian Islands of Vulcano and Stromboli lie north of Sicily, within 12 miles of each other. They have no electricity, no running water and little food or shelter. Every piece of quipment had to be shipped from the mainland aboard fishing smacks. Bergman plays a conniving DP who marries a Strombolian fisherman and has trouble adjusting herself to the rigors of island life.

Magnani plays a prostitute who saves her younger sister from pursuing the same profession. Most of the minor characters are played, neorealist fashion, by the natives.

The shooting of both films proceeded simultaneously and, to Caramelli’s satisfaction, in an atmosphere crackling with rivalry. Reporters were accredited, like war correspondents, to one or the other of the embattled camps.

Generalissimos Rossellini and Dieterle issued weekly communiqués. Partisanship infected the Via Veneto, where Magnaniacs and Bergmaniacs clashed frequently.

Despite their estrangement Magnani still considers Rossellini the greatest director she ever acted for. He still speaks of her as the greatest actress he ever directed, and he recently sent word to her that the would like to produce a picture starring both her and Bergman. Magnani snarled back, “I’ll do it if Ingrid marries me. One of us would have to play the male role”.

“Someday”, she predicts, “when I can look at Roberto objectively, I may act for him again”.

Of further sentimental involvements, however, she says, “I’m finished with men”. Then she adds, “Life is unbearable without love”.

J. Kobler

(All photos © Time Inc. – Life Magazine)